URGENT UPDATE: New research from the University of California, San Francisco reveals that junk food is disrupting our brain’s ability to keep track of time. This groundbreaking study, published in the journal Science, indicates that certain processed dietary fats interfere with the brain’s seasonal timing signals, which could have profound implications for human health.

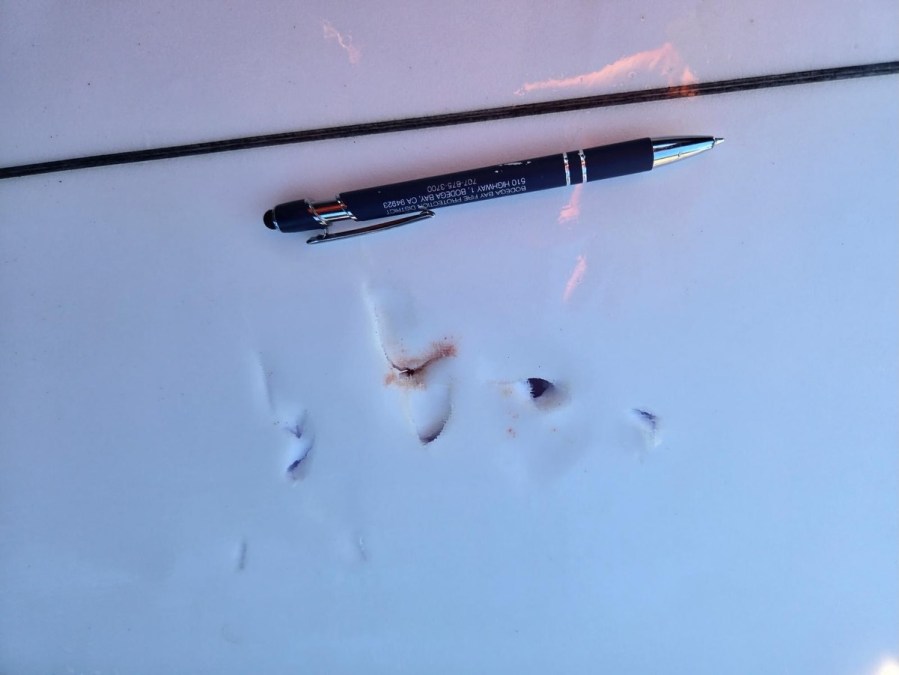

The study focuses on how dietary fat composition affects the internal biological clocks of living organisms. Researchers observed that mice fed diets with identical calorie counts but differing fat ratios showed significant differences in adapting to seasonal light changes. Notably, those consuming fewer polyunsaturated fats took approximately 40 percent longer to adjust to simulated winter lighting conditions, indicating a lag in their internal clocks.

During the experiment, when the lighting shifted to mimic winter, some mice adapted quickly while others struggled, maintaining higher body temperatures and delayed daily rhythms typical of summer physiology. This pivotal difference was attributed not to calorie intake but rather to the type of fat consumed.

In nature, food sources fluctuate with the seasons, with colder months typically providing higher levels of polyunsaturated fats. These fats are crucial for helping tissues function at lower temperatures and serve as biological signals. The researchers found that lower levels of these fats aligned with summer conditions, a time associated with energy storage.

The study traced this seasonal response to a molecular switch in the hypothalamus, a critical brain region governing metabolism and circadian rhythms. This switch responds to nutrient signals, influencing how cells process fats and regulate body temperature. Diets deficient in polyunsaturated fats significantly altered the switch’s activity, changing the expression of hundreds of genes connected to fat signaling.

To validate these findings, researchers examined genetically modified mice incapable of activating this switch. These mice adjusted to seasonal lighting consistently, regardless of their diet, while unmodified mice exhibited varied adjustment speeds based on fat type.

The implications of this research extend beyond animal studies. The team found that food processing exacerbates the issue. For instance, comparing natural corn oil with partially hydrogenated corn oil revealed that the processed version eliminated critical seasonal signals. Hydrogenation alters fat structure for shelf stability, stripping away the chemical cues that indicate winter conditions.

While humans share the same biological pathways, the exact influence of dietary fat on human seasonal rhythms remains untested. The authors caution that these findings do not directly translate into dietary recommendations. However, they underscore a crucial point: modern diets often provide altered fat profiles year-round, regardless of seasonal changes. This constant exposure may disrupt how our internal clocks interpret time.

As the world continues to grapple with health issues linked to diet and lifestyle, this research adds a new layer of understanding to how our bodies respond to food in environments where seasonal variations no longer dictate what we consume.

Stay tuned for further developments on how these findings could influence dietary guidelines and health recommendations.