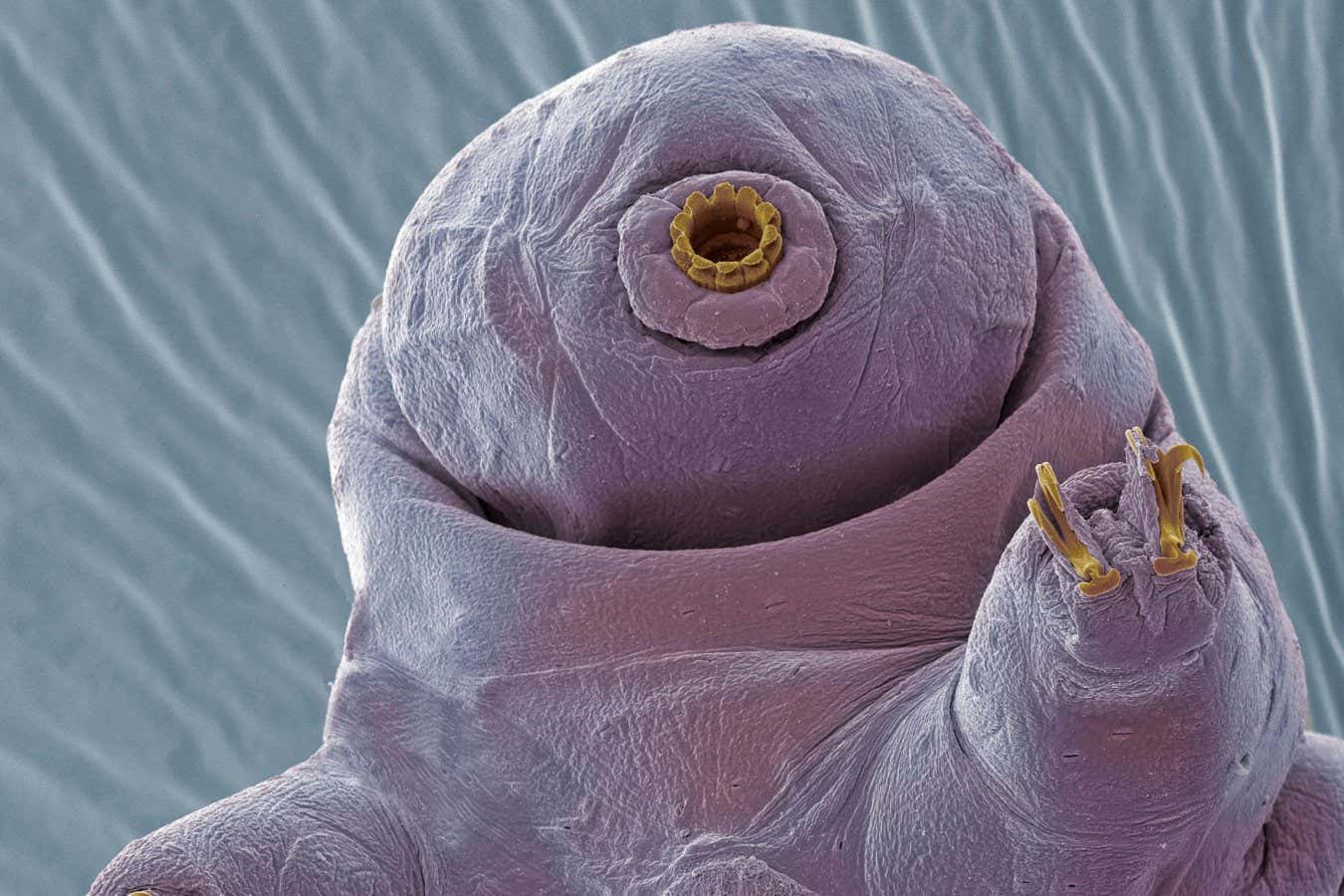

Astronauts may face greater risks from cosmic radiation than previously understood, prompting researchers to explore innovative solutions. A team led by Corey Nislow at the University of British Columbia has revealed that while a protein from tardigrades could offer some protection, using it effectively is more complicated than anticipated.

Tardigrades, often referred to as “water bears,” are renowned for their resilience to extreme conditions, including high levels of radiation and vacuum exposure. The protein in question, known as Dsup, or damage suppressor, has shown promise in protecting cells from radiation and mutagenic chemicals. Research from 2016 indicated that human cells engineered to produce Dsup exhibited enhanced resistance to radiation without observable negative effects. This led to the idea of using Dsup to shield astronauts by administering the protein’s genetic material in the form of mRNA, similar to the technology used in mRNA COVID-19 vaccines.

Nislow initially supported this approach, envisioning a method to deliver Dsup mRNA encased in lipid nanoparticles to astronauts on space missions. However, new findings from his research group have highlighted significant drawbacks. In experiments with yeast cells designed to produce Dsup, researchers discovered that excessively high levels of the protein were lethal, while even moderate levels hampered cell growth.

Nislow explains that Dsup’s protective mechanism involves physically surrounding DNA, which, while shielding it from damage, also complicates access for essential processes such as DNA replication and repair. The research indicated that in cells lacking sufficient DNA repair proteins, the presence of Dsup could lead to fatal consequences.

Despite these challenges, Nislow remains optimistic about the potential applications of Dsup. He suggests that if Dsup production can be regulated to occur only in specific cells and at optimal levels, it may still serve as a viable means of protection for astronauts, animals, and plants in space.

Colleagues are exploring similar avenues. James Byrne from the University of Iowa is investigating whether Dsup can safeguard healthy cells during cancer radiation therapy. Byrne cautions that continuous production of Dsup throughout the human body could have detrimental health effects, yet temporary production during critical moments might yield benefits.

Parallel investigations are being conducted by Simon Galas at the University of Montpellier, who has found that low doses of Dsup can enhance the lifespan of nematode worms by providing protection against oxidative stress. His research underscores the necessity of understanding Dsup’s mechanisms more thoroughly before its application can be considered safe and effective.

Additionally, Jessica Tyler at Weill Cornell Medicine has modified yeast to produce Dsup at lower concentrations than those used in Nislow’s studies. Her findings suggest potential benefits without growth impairment, although she agrees on the importance of achieving the right production levels.

Current technological limitations hinder the ability to control where and how much Dsup is produced within the body. Nonetheless, Nislow expresses confidence that advancements in delivery systems will soon make this possible, acknowledging the significant investment and interest in this area from pharmaceutical developers.

As research unfolds, the complexities of leveraging tardigrade toughness for human application in space exploration will require careful consideration and innovative solutions. The challenge remains to harness the protective properties of Dsup while minimizing its potential drawbacks.