A groundbreaking study has revealed important insights into the formation of Super-Earths. A team of astronomers, led by John Livingston from the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, has published findings in the journal Nature about the exoplanetary system V1298, located approximately 350 light years away in the Taurus constellation. This system is only around 30 million years old and hosts an intriguing collection of four planets that exhibit some of the earliest stages of planet formation observed to date.

V1298’s planets, affectionately dubbed “cotton candy” planets due to their low density, present a unique opportunity for researchers. These large planets, comparable in size to Jupiter, possess surprisingly low mass, reminiscent of a beloved carnival treat. One planet, five times the size of Earth, has a density akin to that of a marshmallow, while the least dense planet is equivalent to cotton candy, with a density of just 0.05 g/cm². This study significantly updates prior mass estimates, which were previously thought to be between 200 and 300 times greater.

The youthfulness of V1298’s star contributes to the complexity of measuring these planets. Young stars frequently exhibit sunspots and flaring activity, which can obscure signals typically used by astronomers to detect exoplanets. To rectify this, the research team utilized data from multiple telescopes, including Kepler, TESS, Spitzer, and the Las Cumbres Observatory. Over the course of nine years, they employed a method known as transit-timing variations (TTVs) to measure the planets’ masses more accurately. This technique observes a planet transiting in front of its star and accounts for gravitational influences from nearby planets.

The research team’s efforts not only refined the mass estimates but also allowed them to “recover” a previously “lost” planet in the V1298 system, which has an orbital period of approximately 48.7 days. Understanding the actual weights of these nascent planets offers vital context for exoplanet evolution.

Astronomers classify exoplanets into two primary categories: Super-Earths and Sub-Neptunes. Super-Earths are generally rocky and less than 1.5 times the radius of Earth, while Sub-Neptunes are gas-rich and about 2.0 times the radius of Earth. Both types typically orbit very close to their stars, often even nearer than Mercury does in our solar system. V1298’s diverse planetary system serves as a model for how these two distinct types of exoplanets can evolve over time.

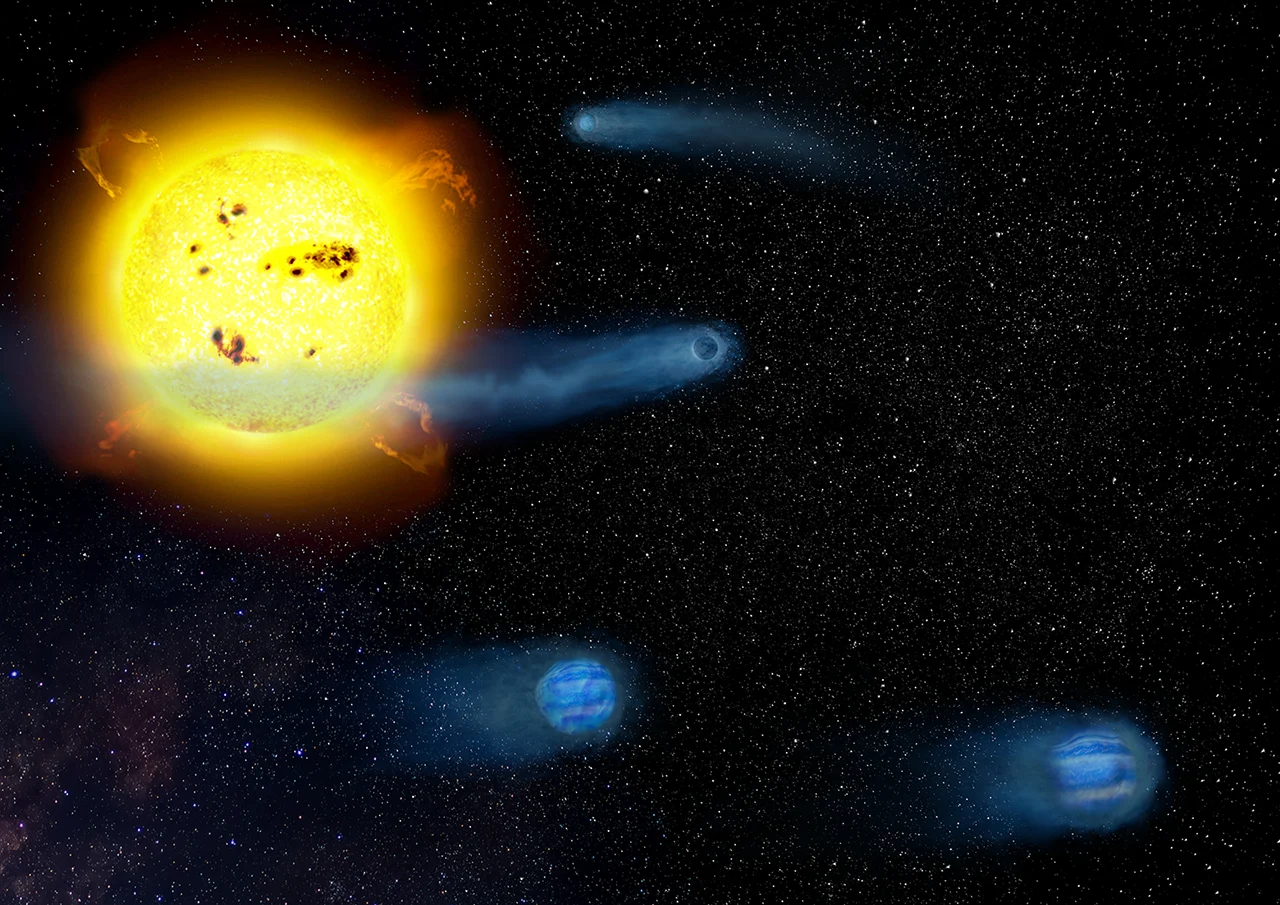

Most astronomers agree that as these planets age, they will gradually lose their atmospheres and shrink. This process is believed to occur through photoevaporation, where radiation from the host star erodes the atmosphere, or via internal heat from the planet’s core pushing the atmosphere away. Both processes can take billions of years. However, the paper suggests a third mechanism, known as “boil-off,” may play a significant role in the early stages of planetary formation. This occurs when a protoplanetary disk, which typically retains a planet’s atmosphere, is dissipated, allowing the atmosphere to escape rapidly, similar to steam escaping from a pressure cooker when the lid is removed.

While V1298 is not the first system to exhibit these processes—Kepler-51 is another well-known example—it is significantly younger, providing unique insights into early-stage planetary development. Some scientists argue that “boil-off” would have concluded in systems like Kepler-51, making V1298 a crucial point of study for understanding the evolution of exoplanets.

The significance of this research is underscored by its acceptance into Nature, one of the world’s leading academic journals. The extensive nine-year data collection reflects the importance of this work, suggesting that it may represent a milestone in the study of exoplanets. There may be additional data on even younger star systems within decades of exoplanet datasets, potentially offering further clues to planetary formation. For now, the V1298 system stands as a vital snapshot of the early stages of planet formation, illuminating our understanding of the cosmos.