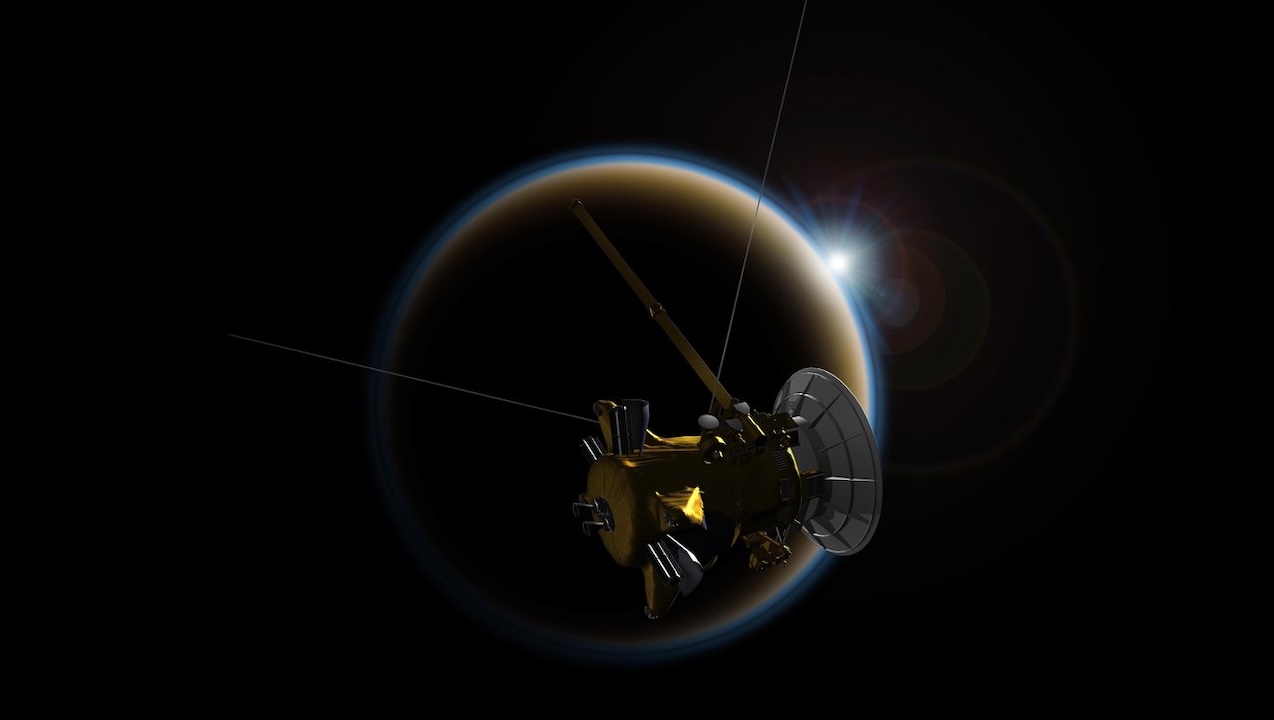

NASA’s Cassini mission, which studied Saturn and its moons from 2004 to 2017, initially suggested that Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, might host a vast ocean beneath its hydrocarbon-rich surface. Recent reanalysis of mission data, however, indicates a more complex structure: Titan’s interior likely consists of ice, slushy layers, and small pockets of warm water near its rocky core. This finding, led by researchers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California, was published in the journal Nature on March 15, 2024, and could reshape scientific understanding of Titan and similar icy moons across the solar system.

The study emphasizes the value of archival planetary science data. “This research underscores the power of archival planetary science data. It is important to remember that the data these amazing spacecraft collect lives on, so discoveries can be made years, or even decades, later as analysis techniques get more sophisticated,” stated Julie Castillo-Rogez, senior research scientist at JPL and a coauthor of the study.

To investigate the interiors of celestial bodies, scientists analyze the radio frequency communications between spacecraft and NASA’s Deep Space Network. This method involves studying the gravitational field fluctuations of a moon as a spacecraft passes through it. Variations in gravity affect the spacecraft’s speed, which alters the frequency of the radio waves—a phenomenon known as Doppler shift. By examining this shift, researchers can infer details about a moon’s gravity field and shape, which may change over time due to its orbit around a planet.

According to the study, the strong tidal response and energy dissipation observed in Titan suggest that a global subsurface ocean is unlikely. Instead, the evidence points to a high-pressure ice layer comprising different types of ice, including ice III, ice V, and ice VI, along with pockets of partial melting. This process, referred to as tidal flexing, occurs as Saturn’s immense gravitational field compresses Titan when it is closer to the planet and stretches it when it is farther away. This flexing generates energy that is dissipated as internal heating.

Initially, scientists concluded that Titan must have a liquid interior because of significant flexing, which would be less pronounced in a solid structure. However, the new research presents an alternative explanation: Titan’s interior likely features a mix of ice and water layers that allow for the observed flexing. This model suggests that the response to Saturn’s tidal pull would lag by several hours, indicating a slower reaction than if the moon had a fully liquid interior.

By applying innovative data processing techniques, researchers led by Flavio Petricca, a JPL postdoctoral researcher, were able to reduce noise in the Doppler data. This refinement revealed a significant energy loss deep within Titan, suggesting the presence of slush layers beneath a thick shell of solid ice. Consequently, the only liquid present would be pockets of meltwater, heated by dissipating tidal energy and potentially enriched with organic molecules.

Petricca noted, “Nobody was expecting very strong energy dissipation inside Titan. But by reducing the noise in the Doppler data, we could see these smaller wiggles emerge. That was the smoking gun that indicates Titan’s interior is different from what was inferred from previous analyses.” He added that the low viscosity of slush allows Titan to bulge and compress in response to Saturn’s tides while managing to dissipate heat that might otherwise create a global ocean.

Despite the absence of a global ocean, researchers remain optimistic about Titan’s potential for hosting life. “While Titan may not possess a global ocean, that doesn’t preclude its potential for harboring basic life forms, assuming life could form on Titan. In fact, I think it makes Titan more interesting,” Petricca stated. The study indicates that pockets of liquid water could reach temperatures of up to 20 degrees Celsius (68 degrees Fahrenheit), cycling nutrients from the rocky core through slushy layers to the solid icy surface.

Future missions may provide more definitive insights into Titan’s structure and habitability. NASA’s upcoming Dragonfly mission, set to launch no earlier than 2028, aims to explore Titan’s surface with a rotorcraft equipped with a seismometer. This mission could yield critical measurements to investigate Titan’s interior, depending on seismic activities during its surface operations.

The Cassini-Huygens mission was a joint project involving NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA), and the Italian Space Agency. Managed by JPL, the mission successfully gathered extensive data about Saturn and its moons, paving the way for future exploration. For more information about the mission, visit NASA’s dedicated page at https://science.nasa.gov/mission/cassini/.