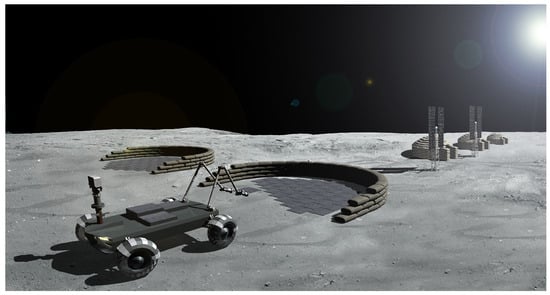

Engineers at Purdue University are advancing efforts to construct the first reusable landing pads on the Moon. A new paper published in Acta Astronautica by Shirley Dyke and her team outlines innovative strategies to utilize lunar materials, or regolith, for building these critical structures. As missions to the Moon become more frequent, the need for durable landing pads to support heavy rockets like Starship is increasingly evident.

The necessity of a landing pad arises from the challenges posed by rocket landings. While it may seem feasible for rockets to land on any flat surface identified by their flight algorithms, the intense force of retrograde rocket plumes can displace significant amounts of dust and debris. This not only risks damaging the rocket itself but also any nearby infrastructure, such as future lunar bases. Thus, mission planners are united in their belief that a structured landing pad is essential.

Current Earth-based landing pads are well-understood and have proven effective for decades. However, replicating these using lunar materials presents unique challenges. Transporting concrete from Earth for construction would be prohibitively expensive, making it imperative to leverage local resources. According to Dr. Dyke, the mechanical properties of lunar regolith remain largely unknown, particularly regarding how the material behaves when sintered—a process crucial for creating a solid structure from in-situ materials.

Testing simulants, which closely resemble lunar regolith, has been a go-to approach for preliminary studies. Yet, Dr. Dyke cautions that simulants cannot fully replicate the unique conditions on the Moon. The only way to accurately assess how the material will react is through in-situ testing.

Design Considerations for Lunar Landing Pads

When designing a landing pad, engineers must consider both mechanical and thermal properties. The mechanical properties relate to how the material responds under stress, while thermal properties involve how it expands and contracts with temperature fluctuations. Although there is limited data on sintered regolith, the team has made estimates based on existing literature.

Initial theories suggest that sintered regolith might exhibit brittleness, with greater strength under compression than tension. Additionally, it is anticipated to have high thermal insulation properties, meaning that only the top layers would experience significant temperature increases during rocket landings. However, repeated landings could lead to cracking and degradation of the pad over time.

The lunar day-night cycle, lasting 28 Earth days, introduces another critical factor. Temperatures can vary dramatically, causing expansion and contraction that could lead to warping if not evenly distributed throughout the pad. The authors recommend a thickness of approximately 1/3 meter (about 14 inches) for a landing pad designed to support a 50-ton lander. Dr. Dyke explained that making the pad thicker could inadvertently increase its likelihood of failure due to thermal stresses.

While some failure modes are anticipated, such as spalling—where fragments of the pad chip off—the primary concern remains the potential for catastrophic fracturing. This could result from thermal stresses, the weakening of the material from repeated landings, or an improper landing angle.

Future Steps for Lunar Exploration

To mitigate these risks, the authors advocate for a phased approach involving in-situ testing during initial lunar missions. Early explorations could focus on gathering data about the regolith and its properties in the lunar environment. This would allow engineers to refine their understanding and improve designs for landing pads.

Once a pad is constructed, continuous monitoring and data collection would be essential. Dr. Dyke aims to focus on how the pad deforms under load and during extreme temperature cycles. Understanding these dynamics will be crucial for predicting crack formation and developing strategies to manage them.

The construction and maintenance of lunar landing pads will likely rely heavily on robotic technology. With the complexities of working in a harsh lunar environment, teleoperated or autonomous robots will play a vital role in both building the pad and ensuring its longevity.

Despite the distance from launching the first lunar landing pad, NASA and other organizations are making strides toward returning astronauts to the Moon. As this process unfolds, researchers on Earth hope to gather more data to enhance their models of how landing pads might function in the lunar landscape. The iterative testing and design approach proposed in Dr. Dyke’s research could ultimately lead to a safe and effective entry point to our nearest celestial neighbor.