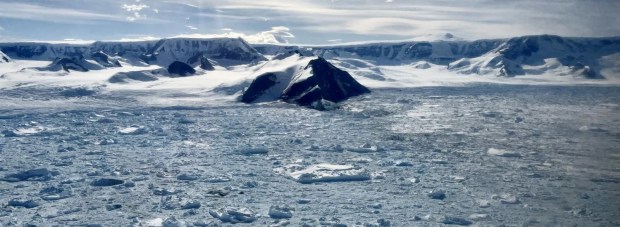

A research team at the University of Colorado Boulder has identified a rapid retreat process affecting the Hektoria Glacier in Antarctica, leading to a significant loss of its mass. The glacier, which is grounded on bedrock, lost approximately half of its total mass, retreating about 15.5 miles between January 2022 and March 2023. This phenomenon marks the fastest retreat ever recorded for a grounded glacier.

Research Affiliate Naomi Ochwat observed the glacier’s unprecedented speed of retreat while monitoring various glaciers in Antarctica. Intrigued by the data, she investigated further to understand the underlying causes. “This process, if it could occur on a much larger glacier, then it could have significant consequences for how fast the ice sheet can change as a whole,” Ochwat noted, highlighting concerns about potential impacts on global sea levels.

The Hektoria Glacier, measuring about 8 miles across and 20 miles long, is relatively small compared to other Antarctic glaciers. While its retreat contributes minimally to sea level rise—amounting to fractions of a millimeter—researchers emphasize the importance of understanding the mechanisms behind such rapid changes.

The research revealed that the glacier’s ice tongue, which extends into the ocean, began to disintegrate as warmer conditions caused a layer of fast ice to break away. This fast ice is essential for supporting the glacier. As the fast ice diminished, the underlying ice became destabilized, leading to a cascade of ice slabs breaking off. Senior Research Scientist Ted Scambos described this process as akin to “dominoes falling over backwards.”

The Mechanism Behind the Retreat

While the retreat itself is not unusual, the mechanisms at play are noteworthy. The study found that the rapid retreat was primarily driven by the calving process of the ice plain beneath the glacier, rather than atmospheric or oceanic conditions. Satellite-derived data, such as imagery and elevation measurements, were instrumental in the research.

This calving process has not been observed before in glaciers of this type, indicating a potential vulnerability for other glaciers resting on similar ice plains. Historical data suggest that during previous warm periods, Antarctic glaciers with ice plains retreated hundreds of meters per day, providing context for the Hektoria Glacier’s current behavior.

“The fact that Hektoria retreated and dumped a bunch of ice into the ocean doesn’t really change much, to be completely honest,” Ochwat stated. “The important aspect is this mechanism that leads to rapid retreat, which has not been documented previously.”

Global Implications of Glacier Retreat

The implications of such rapid glacier retreat extend beyond Antarctica. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, nearly 30% of the U.S. population resides in coastal areas, where rising sea levels contribute to flooding, shoreline erosion, and increased storm hazards. Globally, eight of the world’s ten largest cities are positioned near coastlines, as noted in the United Nations Atlas of the Oceans.

Scambos emphasized the importance of recognizing this phenomenon: “It meant this grounded glacier lost ice faster than any glacier had in the past. It’s crucial to identify other regions in Antarctica where this process might occur.”

Researching these mechanisms is vital, as Ochwat explained: “What happens in Antarctica does not stay in Antarctica. There’s so much we don’t know, and the potential effects could be profound.” Understanding the dynamics of glaciers like Hektoria is essential for predicting future changes in sea levels and their impacts on global communities.