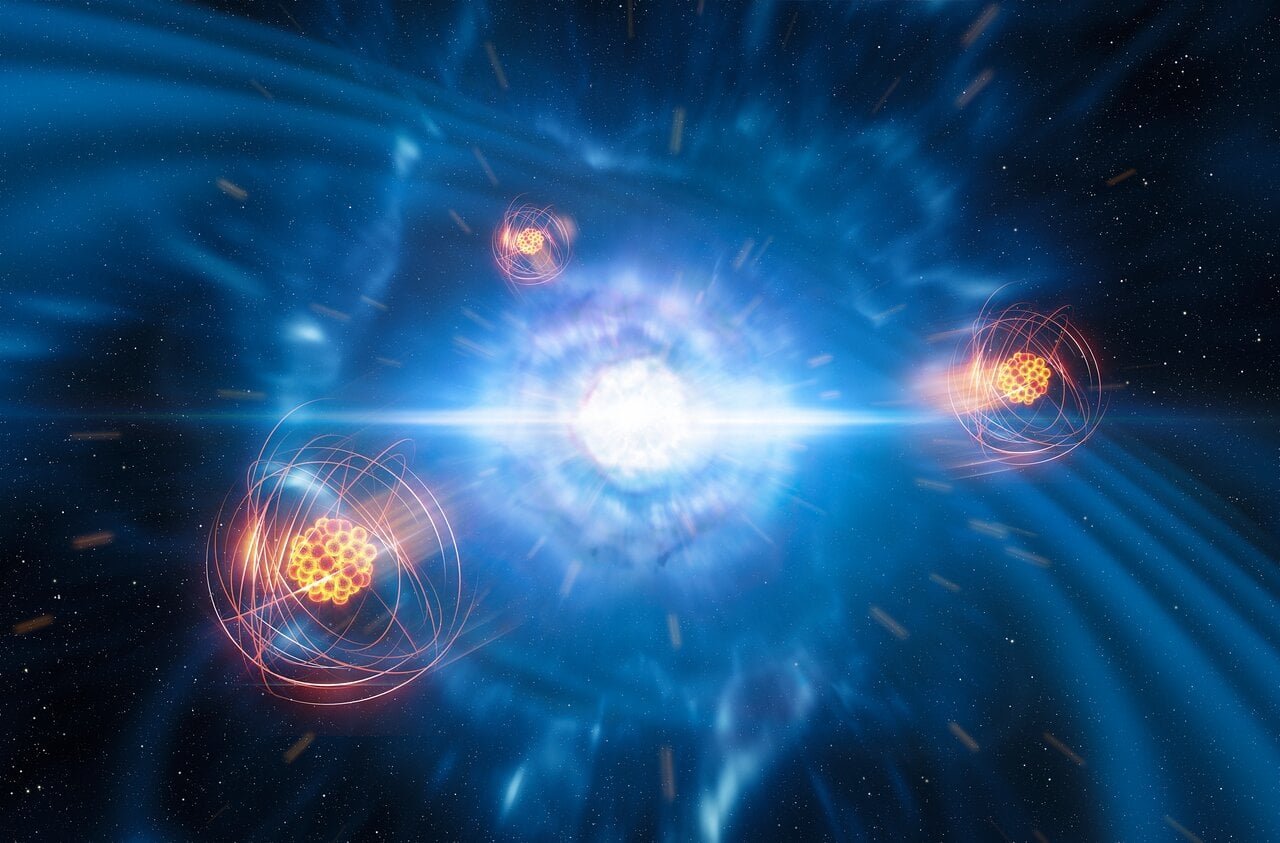

Recent research has proposed that cosmic rays from distant supernovae may play a crucial role in the formation of Earth-like planets. This new study challenges existing theories by suggesting that rather than being destroyed by shockwaves from a nearby supernova, the early solar system was enriched by cosmic rays, leading to the necessary conditions for terrestrial planets.

The study, conducted by Ryo Sawada and colleagues, highlights that to create an Earth-like planet, several factors must align. A planet must possess sufficient mass to retain an atmosphere and generate a magnetic field, yet not so much mass that it retains lighter elements like hydrogen and helium. Additionally, it must orbit its star at a distance that allows for liquid water while avoiding excessive heat that could evaporate it.

An essential component in this equation is the presence of short-lived radioisotopes (SLRs), which have half-lives of less than five million years. These isotopes contribute to warming the early solar system, preventing terrestrial planets from accumulating excessive water. The study indicates that without SLRs, many Earth-sized planets would transform into “Hycean” worlds, characterized by deep oceans and likely inhospitable conditions.

Numerous meteorites provide evidence that the solar system was previously rich in SLRs. For instance, the isotope aluminum-26 decays into magnesium-26, and an excess of magnesium in a meteor fragment indicates the historical presence of radioactive aluminum. Other isotopes, such as titanium-44, follow similar decay processes, further supporting the notion of SLR abundance.

Cosmic Rays and Planet Formation

A significant concern regarding the formation of SLRs is their origin in supernovae. Typically, nearby supernovae would disrupt the protoplanetary disk of a young star, complicating the formation of stable planets. However, the new model proposed by Sawada and his team suggests that if at least one supernova occurred within a parsec of the early solar system, it could have provided the necessary cosmic rays to create sufficient levels of radioactive isotopes.

This model posits that rather than experiencing destructive shockwaves from a nearby supernova, the solar system was instead bathed in beneficial cosmic rays from a more distant supernova. The researchers argue that because sun-like stars often form in clusters, the likelihood of encountering a supernova within a parsec is relatively high. This increases the probability of forming terrestrial planets similar to Earth.

According to the research, the enrichment of the galaxy with radioactive aluminum can provide insight into the frequency of supernovae in the Milky Way. The presence of aluminum-26 within the galaxy suggests that the rate of supernovas aligns with the findings of this study, making the scenario highly plausible.

The implications of this research extend beyond theoretical astrophysics. Understanding the conditions that lead to the formation of Earth-like planets can inform future explorations in the search for extraterrestrial life. If such planets are indeed common, they may provide habitats capable of supporting life as we know it.

The findings of this study were published in the journal Science Advances, marking a significant contribution to our understanding of planetary formation and the factors that contribute to the emergence of Earth-like worlds. As research continues to evolve, the prospect of discovering similar planets within accessible distances in the galaxy becomes increasingly feasible.