The United States has announced a significant shift in its nuclear policy with President Donald Trump‘s recent declaration to resume underground nuclear testing, the first such move since September 1992. This decision comes as a response to advancements in nuclear capabilities by both Russia and China, who have refrained from nuclear testing despite the ongoing implications of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, which, while not fully in force, has established a global norm against such activities.

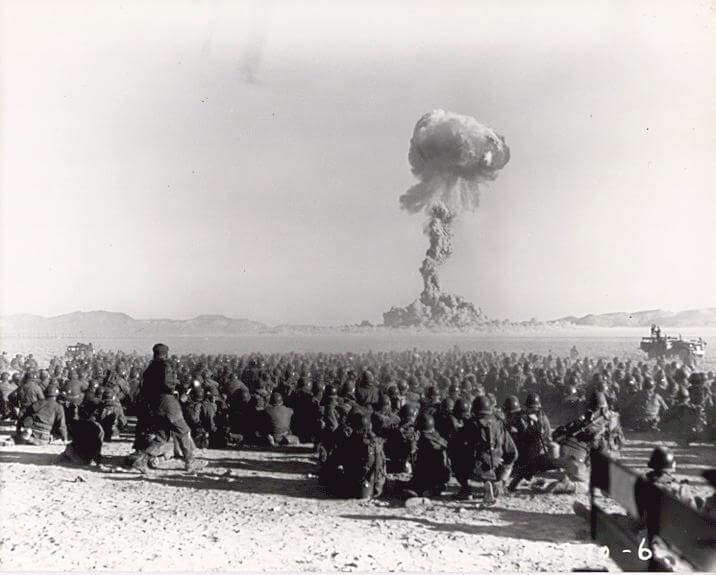

Historically, the U.S. maintained a robust nuclear testing program, conducting a total of 828 underground tests at the Nevada Test Site from 1945 to 1992. This moratorium has allowed the U.S. to rely on a science-based stockpile stewardship program managed by the Department of Energy and the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), assessing the reliability and effectiveness of its nuclear arsenal without reverting to actual tests.

The implications of resuming nuclear tests are significant and multifaceted. Analysts warn that if the U.S. proceeds with testing, other nuclear-armed states may feel compelled to follow suit, potentially igniting a new arms race. The last nuclear tests by Russia occurred in 1990, while Pakistan, China, and France concluded their testing between 1996 and 1998. The only nation that has continued testing is North Korea, with six tests conducted from 2006 to 2017.

Understanding the Strategic Landscape

The recent announcement raises critical questions about the current state of global nuclear arsenals. As of 2023, the U.S. reportedly possesses 3,748 active and inactive warheads, according to the Department of Energy. The precise size of the Russian nuclear stockpile remains unclear, as Russia has halted data exchanges mandated by the New START Treaty. Additionally, estimates suggest that China could have over 600 operational nuclear weapons and may exceed 1,000 by 2030.

While Trump’s statement emphasized a desire for “testing on an equal basis” with other nations, details on what constitutes this testing remain vague. If the U.S. intends to conduct underground detonations involving critical nuclear materials and neutron release, this would mark a significant departure from the current stewardship program, which avoids such criticality.

Though the Department of Defense has been assigned the task of resuming testing, the NNSA retains the necessary expertise to conduct these operations. The infrastructure for testing has deteriorated since the last U.S. test in 1992, with much of the specialized knowledge lost due to retirements and reassignments within the workforce.

Environmental and Global Implications

The potential environmental consequences of renewed nuclear testing are concerning. Past tests have left a legacy of radiological contamination, with even contained underground tests emitting tritium and other radioactive byproducts that can spread beyond the test site. As the world grapples with pressing issues such as access to fresh water and arable land, the risks posed by nuclear testing could extend far beyond national borders.

Critics argue that the resumption of nuclear tests contradicts the U.S. administration’s diplomatic objectives to reduce regional tensions and conflicts. Renewed testing could exacerbate fears regarding nuclear weapon use and inadvertently encourage other nations to pursue their own nuclear ambitions, particularly in regions like Asia-Pacific, the Arabian Gulf, and Europe.

The U.S. has invested over $30 billion in its current stockpile stewardship program, which has maintained the safety and reliability of its nuclear arsenal without the need for testing since 1992. Instead of resuming tests, experts advocate for strengthening monitoring and forensic capabilities to detect and attribute any future tests unequivocally.

As this situation unfolds, the international community will watch closely to see how the U.S. balances its nuclear strategy with the need for global stability and nonproliferation efforts. The most impactful demonstration of nuclear capability may not be the act of testing but rather the commitment to uphold peace and security without resorting to nuclear trials.