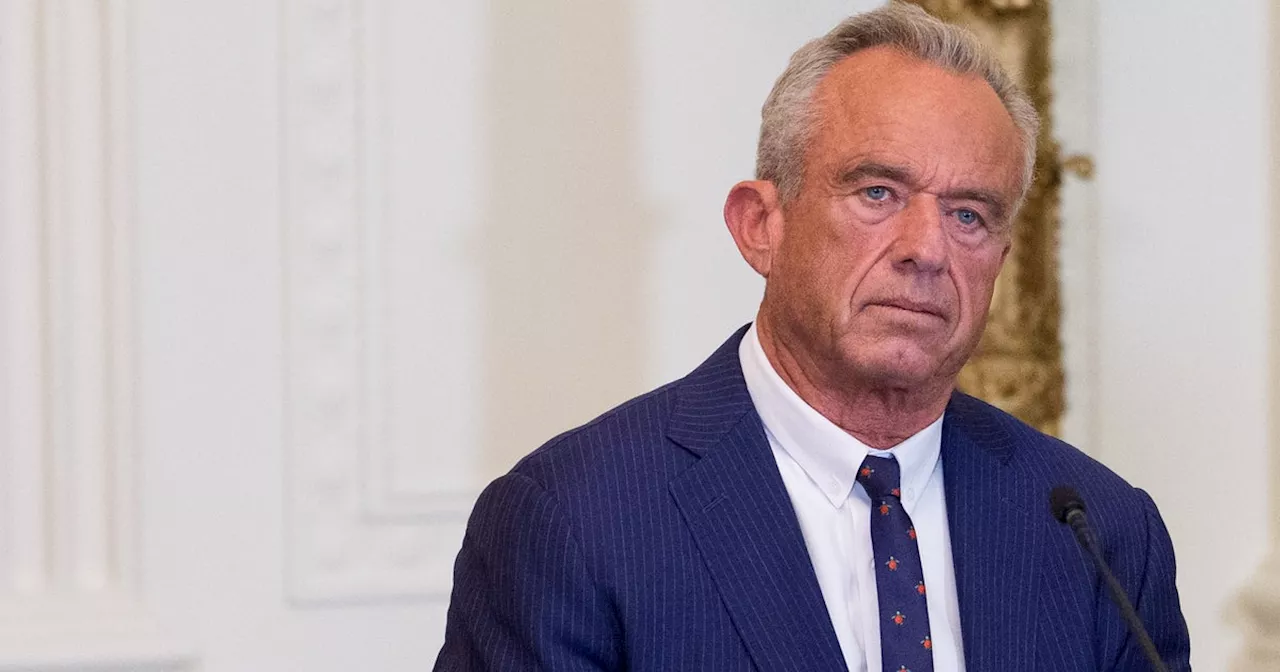

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. recently asserted that the ketogenic diet could “cure” mental illnesses, including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. During a speech, Kennedy claimed, “We now know that the things that you eat are driving mental illness in this country.” He referenced research from Harvard University, stating that some patients have seen improvements in their mental health through dietary changes. However, experts in the field of mental health and nutrition are challenging these assertions, emphasizing that the claims are exaggerated and lack robust scientific support.

Understanding the Claims

Kennedy’s comments align with the ideology of his “Make America Health Again” campaign, which promotes the belief that natural foods are superior for health. He emphasized a diet rich in “real food”—including proteins, fruits, vegetables, and high-fiber grains—as beneficial for mental health. According to Kennedy, recent studies indicate that individuals can lose their bipolar diagnosis by altering their diet.

Experts, however, caution against the use of the term “cure.” Dr. Lippman-Barile, a specialist in nutritional psychiatry, noted that while there is some evidence suggesting that ketogenic diets may assist in treating certain mental health conditions, the findings are often based on small sample sizes or short durations. She stated, “We also have no long-term studies looking at the keto diet and what that does for mental illness.”

The Evidence Behind Dietary Interventions

While there is ongoing research into how nutrition affects mental health, experts assert that dietary modifications should not replace traditional treatment methods. Dr. Ramsey, a psychiatrist who integrates nutritional psychiatry into his practice, explained that dietary interventions are most effective when used alongside evidence-based treatments such as medication or therapy. He remarked, “We’ve known that a ketogenic diet and dietary interventions are really important and can be helpful in augmenting care and mental health.”

Ramsey highlighted the Mediterranean diet as an example where symptoms of depression improved when combined with other treatments. He reiterated that, while the ketogenic diet may be beneficial for some patients, it should not be classified as a “cure.” “Treatment doesn’t lead to a cure. Instead, it leads to recovery,” he stated.

The relationship between diet and mental health is complex. Individuals with digestive disorders, for instance, are at an increased risk of depression and anxiety. Lippman-Barile emphasized that while there is a connection between stress management and diet, this does not mean that a ketogenic diet is a standalone solution for mental health issues.

The Bigger Picture

Kennedy’s claims about the ketogenic diet have sparked concern among health professionals, who argue that sensationalist statements can mislead the public. The standard American diet is often criticized for its lack of nutrition, and any dietary change that emphasizes whole foods over processed options can yield improvements in mental health outcomes.

Dr. Ramsey pointed out, “If you eat real food—more protein, more vegetables, and fewer processed foods—you will have better mental health outcomes.” This does not imply that dietary changes alone are sufficient for treating complex mental health disorders.

Experts unanimously agree that mental illnesses are multifaceted and cannot be addressed with a single intervention. Lippman-Barile explained, “There’s no one solution. ‘Holistic,’ evidence-based care is a variety of interventions.” This may include medication, exercise, therapy, and dietary changes.

In conclusion, while the ketogenic diet and other nutritional strategies may play a role in a comprehensive treatment plan for mental health disorders, claims of it being a cure are unfounded. As research continues to evolve, it is crucial for health communications to remain grounded in evidence-based practices to ensure patient safety and effective treatment.