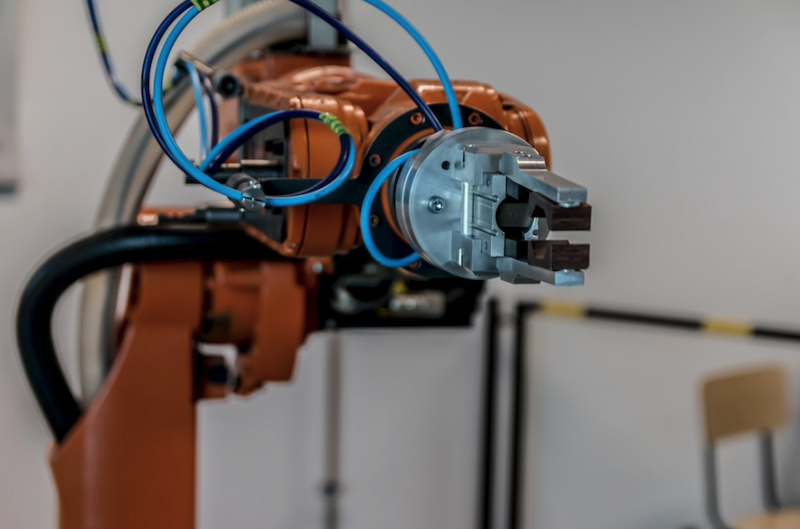

As manufacturing technology evolves with the integration of smart CNC systems and industrial robots, the significance of tool geometry persists. Despite advancements in automation, the fundamental principles of cutting remain unchanged, emphasizing that the selection and design of cutting tools play a pivotal role in production efficiency.

Fundamentals of Cutting Tools in Automated Processes

Advanced systems now allow robots to load parts and CNC controls to adapt feeds and speeds in real time. Nevertheless, the core physics of chip formation still relies heavily on tool geometry, which encompasses attributes such as helix angles, rake angles, flute count, and edge preparation. These factors determine cutting forces, heat generation, chip flow, and surface finish. If the geometry is flawed, the sophisticated software can only mitigate the resulting inefficiencies rather than resolve them.

Research conducted by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) illustrates the complexities of smart manufacturing environments. In these setups, AI and sensors monitor machining conditions to optimize performance. However, a sound process begins with appropriate tool selection. For instance, a recent study highlighted that optimizing tool micro-geometry can significantly reduce cutting forces and improve surface quality, ultimately extending tool life.

The Impact of Tool Geometry on Production Efficiency

In high-mix job shops, where the manufacturing of various components occurs in quick succession, the choice of tool geometry becomes crucial. A nominally similar tool, such as a 10 mm carbide end mill, can yield vastly different results based on its specific design features. For example, a high-helix, polished 3-flute end mill is typically more effective for machining aluminum than a standard 4-flute design.

A practical understanding of these variations can prevent operational failures. For instance, in a fully automated environment, robots lack the ability to adjust based on subtle cues that a human operator might notice, such as unusual sounds. Therefore, effective tool geometry—such as incorporating small corner radii to reduce stress and prevent chipping—is essential for maintaining production stability.

The efficacy of flute count is equally important. In tight machining pockets, designs that facilitate chip evacuation, such as 2- or 3-flute tools, can enhance performance, whereas a 4-flute design may inadvertently lead to excessive heat build-up and chatter. This highlights how careful selection of geometry can avert costly downtime and maximize efficiency.

Incorporating smart tools into manufacturing processes necessitates a structured approach to tool geometry. Manufacturers are encouraged to establish standardized “tool families” based on material and operation, rather than simply diameter. For instance, defining specific geometries for aluminum machining can significantly improve process reliability.

As organizations strive to leverage the full capabilities of AI and robotics, they should also integrate geometry considerations into their process approval workflows. This involves reviewing not only feeds and speeds but also helix angles, flute counts, and edge design for every primary cutter.

To enhance future projects, businesses should document successful tool geometries that consistently yield superior performance. By developing a library of effective geometries, companies can establish best practices that align with their automated systems, ultimately enhancing productivity and reducing waste.

In conclusion, while smart CNC controls and industrial robots are revolutionizing manufacturing, tool geometry remains a fundamental aspect of the cutting process. Recognizing its importance as a primary design consideration rather than an afterthought allows manufacturers to maximize the benefits of their automation investments.