The discussion surrounding the United States’ military strategy in Greenland has intensified, particularly under former President Donald Trump. A key argument presented is that acquiring Greenland is essential for the U.S. to safeguard itself against missile attacks. However, experts argue that this notion is misguided and could actually undermine U.S. national security.

One of the central elements in this debate is the Golden Dome missile defense system, which aims to protect the U.S. from various missile threats, including ballistic missiles and drones. Despite its ambitious objectives, details about the program remain murky. The House and Senate appropriators highlighted concerns in the fiscal defense appropriations bill, stating that they were unable to effectively assess resources available for Golden Dome due to “insufficient budgetary information.” They expressed support for the program’s operational goals but emphasized the need for clearer oversight.

The U.S. military has a long-standing presence in Greenland, dating back to World War II and the Cold War. The current military agreement between the U.S. and Denmark, established in 1951, allows the U.S. considerable flexibility regarding military operations in Greenland. It permits the construction and maintenance of military facilities, as well as the right to manage defense areas.

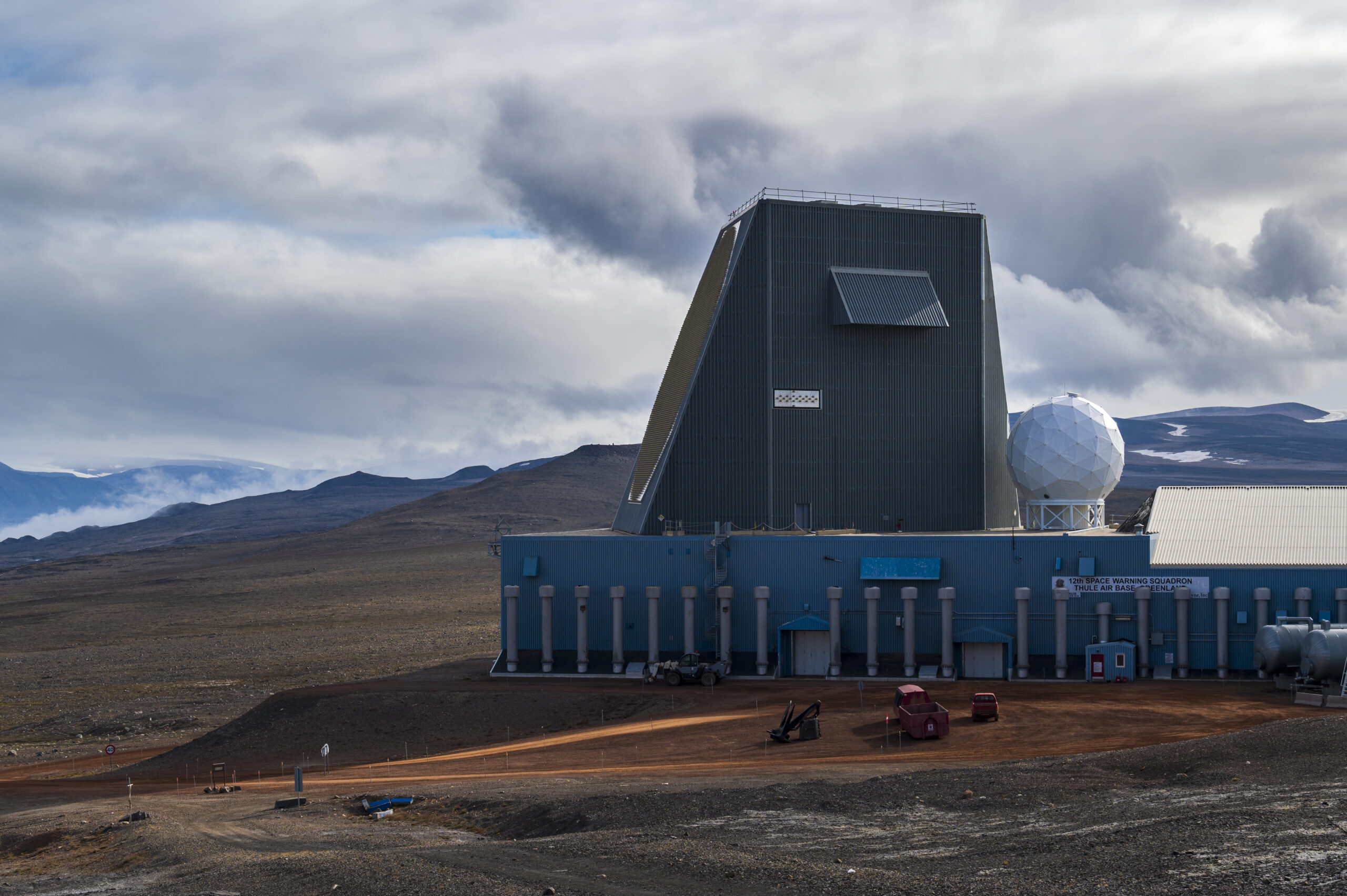

Golden Dome envisions a multilayered defense system incorporating various existing frameworks, including the Ground-based Midcourse Defense (GMD) system. This system is designed to defend against intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and includes four interceptor layers—three land-based and one space-based. It also plans to utilize existing sensors, like the radar at the Pituffik Space Base in Greenland, which has been part of the U.S. early-warning network for decades.

Despite the potential for expanding military capabilities in Greenland, experts question the necessity of establishing new interceptor sites there. The U.S. already operates 44 GMD interceptors in Alaska and California. Additionally, there are plans for a new interceptor site at Fort Drum, New York, which could fulfill any strategic needs for a more northern position without the complications of acquiring Greenland.

The argument for forcibly annexing Greenland is further complicated by its implications for U.S. relations with NATO allies. Experts caution that such a move could weaken the military alliance that has been pivotal for over seventy years. Gen. Chance Saltzman, Chief of Space Operations for the Space Force, emphasized the importance of international partnerships, stating, “Spacepower is the ultimate team sport.” He highlighted that cultivating relationships with allies is essential for achieving U.S. interests in space.

The challenges associated with Golden Dome extend beyond its feasibility and cost. Critics also raise concerns about its technical complexity and the potential for increasing the militarization of space. As Victoria Samson, Chief Director of Space Security and Stability for the Secure World Foundation, and Krystal Azelton, Senior Director of Program Planning, pointed out, these factors should not be used to justify territorial expansion at the expense of a NATO ally.

In conclusion, while the U.S. military’s strategic posture in Greenland warrants serious consideration, the notion of annexing the territory raises significant questions about its necessity and the broader implications for national and international security. As the situation develops, a careful evaluation of military needs, international partnerships, and diplomatic relations will be essential for guiding future decisions.