For the first time, scientists have constructed a three-dimensional representation of the sun’s internal magnetic field, utilizing nearly three decades of satellite data. This breakthrough enables researchers to better understand the underlying mechanisms behind the sun’s changing behavior, including the formation of dark spots and solar flares.

Revolutionizing Solar Studies

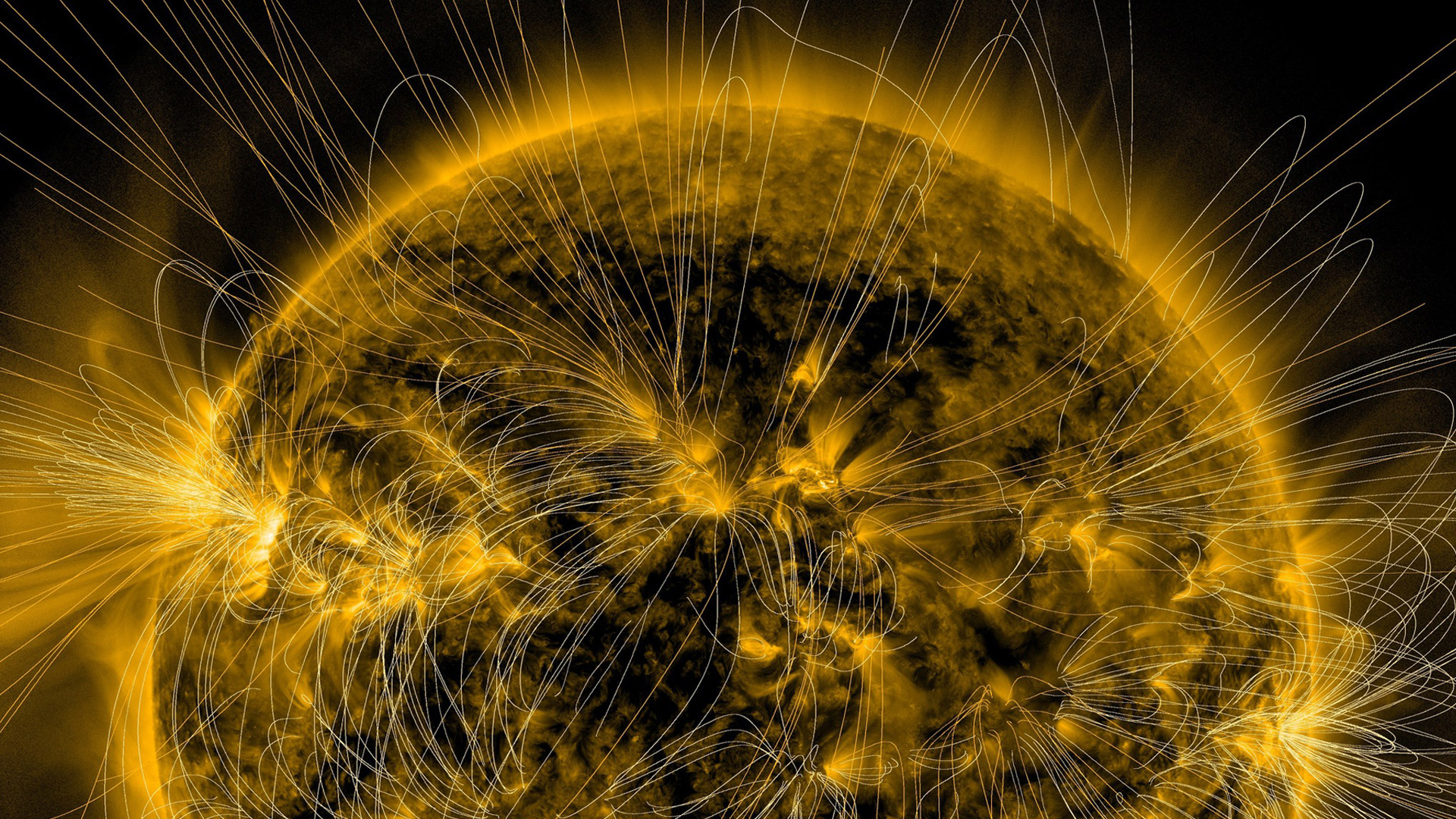

The sun’s magnetic field, created by the movement of electrically charged gas in its interior, has traditionally been difficult to study. While it is known that this process, termed the solar dynamo, occurs deep within the sun, no instruments have been able to directly measure the magnetic fields that exist below its visible surface. Until now, scientists relied on surface observations to infer activity taking place beneath.

In this pioneering study, researchers employed a novel approach. They compiled daily magnetic field maps captured by solar satellites from 1996 to 2025. These maps documented the appearance and evolution of magnetic fields on the sun’s surface over time. The study authors integrated this data into a comprehensive three-dimensional computer model, designed to replicate the sun’s internal magnetic systems.

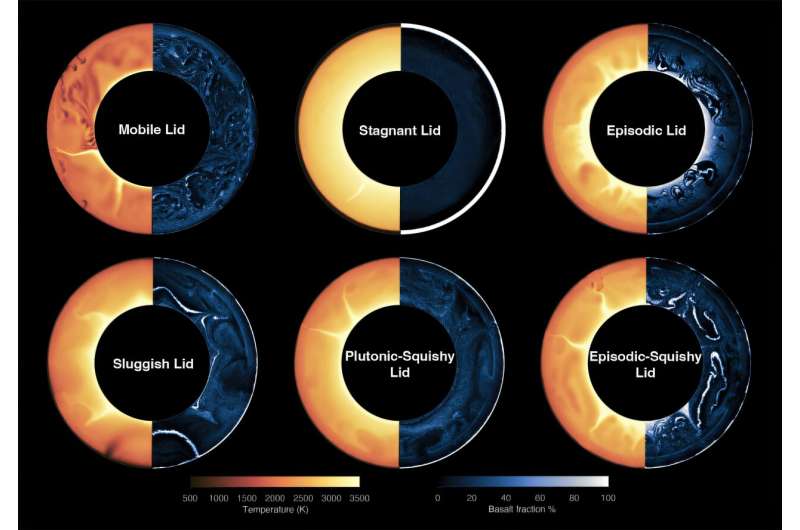

The model continuously adjusted itself based on incoming data, allowing researchers to reverse-engineer the magnetic structures and flows that likely exist beneath the surface. They then validated their approach by asking the model to reconstruct past solar cycles, which span approximately 11 years and are characterized by fluctuating solar activity.

Success in Predictive Modelling

The model proved successful, accurately reproducing notable solar cycles observed during the satellite era. Key indicators, such as the movement of sunspots from higher latitudes toward the solar equator, were effectively captured. The authors stated, “Our data-driven model successfully reproduces key observational features, such as the surface butterfly diagram, accurate polar field evolution, and axial dipole moment.”

As a final test, the researchers paused the introduction of new data and allowed the model to project future solar activity independently. Remarkably, it accurately predicted significant solar features three to four years in advance. The study highlights a strong correlation between the simulated toroidal magnetic field and sunspot numbers, establishing the model as a robust tool for forecasting solar cycles.

This research marks a significant advancement in solar studies. By moving away from viewing the sun’s interior as an enigmatic area, scientists can now monitor it indirectly and continuously. Improved forecasts of solar activity could enhance the protection of satellites, mitigate risks to navigation systems, and provide power grid operators with early warnings about geomagnetic disturbances.

Looking ahead, the researchers aim to refine their technique to predict not only when solar activity will peak but also the locations on the sun’s surface where active regions are likely to develop. The study has been published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, indicating a promising direction for future solar research.

While the model shows great potential, its effectiveness hinges on the continuity of long-term satellite missions. As advancements in this field progress, the opportunity for more precise solar activity predictions could revolutionize our understanding and preparedness for solar phenomena.