Low-Earth orbit (LEO) is on the brink of disaster, with researchers estimating that a catastrophic satellite collision could occur in just 2.8 days. This alarming conclusion comes from a study conducted by Sarah Thiele, a researcher at Princeton University, and her team, who emphasize the fragile nature of current satellite networks. The findings, which are detailed in a paper available as a preprint on arXiv, highlight an urgent need for improved monitoring and management of satellite operations.

Satellite networks in LEO, including large constellations like Starlink, are more crowded than ever. Satellites frequently come within 1 kilometer of each other, with “close approaches” occurring approximately every 22 seconds across all mega constellations. In the case of Starlink, this happens every 11 minutes. To prevent collisions, each Starlink satellite must perform an average of 41 course corrections annually. While this may suggest effective operational protocols, it raises concerns about the risks associated with rare, disruptive events.

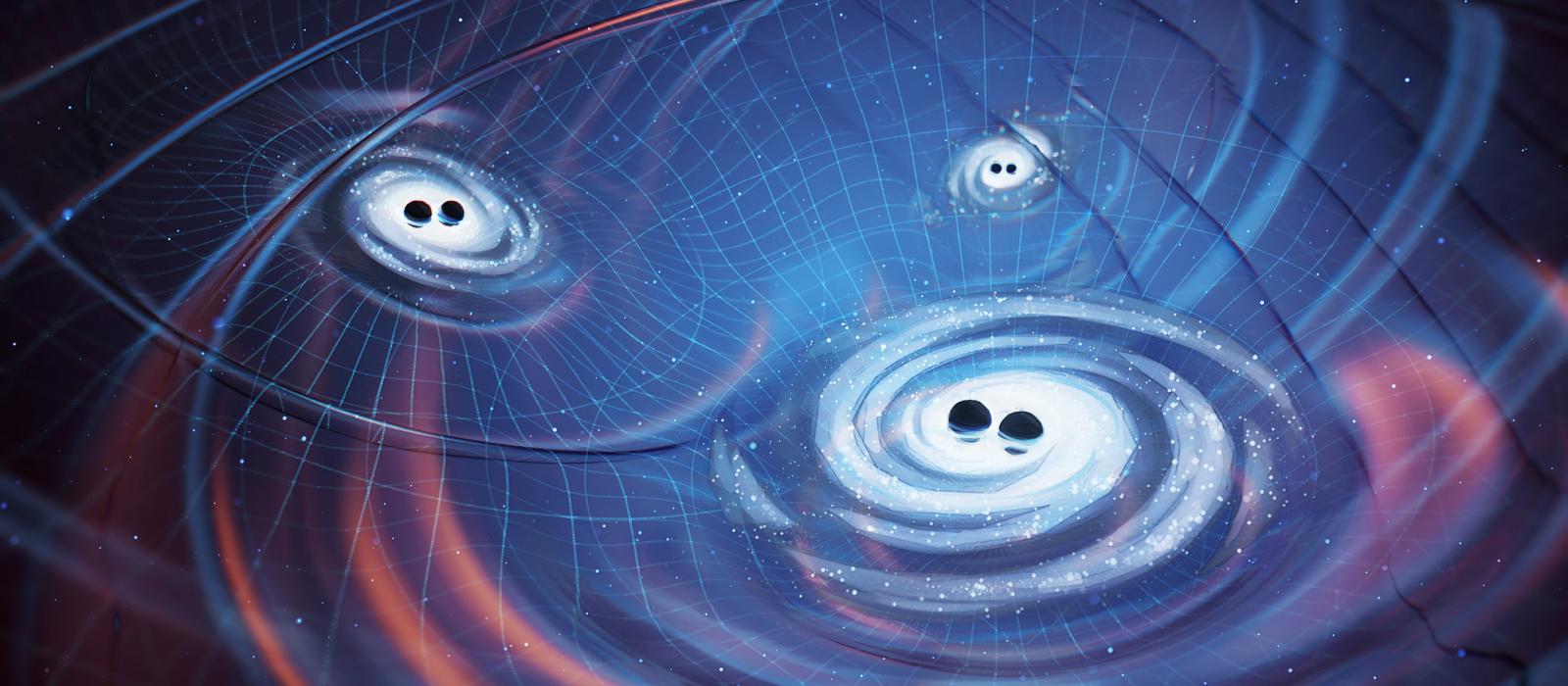

Solar storms present a significant risk to satellite operations. These storms can disrupt satellite navigation and communication systems, rendering them unable to respond to potential threats. During the Gannon Storm in May 2024, more than half of the satellites in LEO had to burn fuel to adjust their trajectories. This scenario exemplifies how atmospheric changes during solar storms can increase drag on satellites, forcing them to use more fuel and complicating their positional accuracy.

The research introduces a new metric called the Collision Realization and Significant Harm (CRASH) Clock, which measures the timeline to catastrophic collisions under certain conditions. According to the study, if control over satellite maneuvering is lost, a catastrophic collision could occur in as little as 2.8 days. In contrast, prior to the rise of mega constellations in 2018, similar conditions would have allowed for around 121 days before such a disaster unfolded. The risk escalates further; losing control for just 24 hours carries a 30% chance of a major collision.

Warnings about solar storms typically come only a day or two in advance, leaving satellite operators with limited options for mitigating risks. The rapidly changing atmospheric conditions demand constant real-time monitoring and control. If this control is lost, the window for recovery could be as short as a few days before a system-wide collapse occurs.

The potential ramifications of a severe solar storm could be devastating. The strongest storm on record, the Carrington Event of 1859, serves as a historical reminder of the serious threats posed by such events. If a storm of similar magnitude were to strike today, it could severely disrupt satellite control for an extended period, potentially leading to widespread failures and limiting humanity’s access to space for generations.

As satellite mega constellations become increasingly integral to our technological landscape, understanding the associated risks is crucial. While these networks offer tremendous benefits, the prospect of being cut off from space due to a single extreme solar storm underscores the necessity for informed decision-making in space infrastructure management. This research paints a vivid picture of the stakes involved and emphasizes that the risks posed by our interconnected sky can no longer be overlooked.

In summary, the study prompts a reevaluation of how satellite operations are managed, especially in light of the growing threats posed by solar storms and the increasing density of satellite networks in Low-Earth Orbit.