A recent study has established a significant connection between experiences of peer victimization and increased depressive symptoms among Brazilian adolescents. Conducted by the Ministry of Health, this extensive research examined data from over 165,000 youths across Brazil, revealing concerning trends that highlight the mental health challenges faced by students.

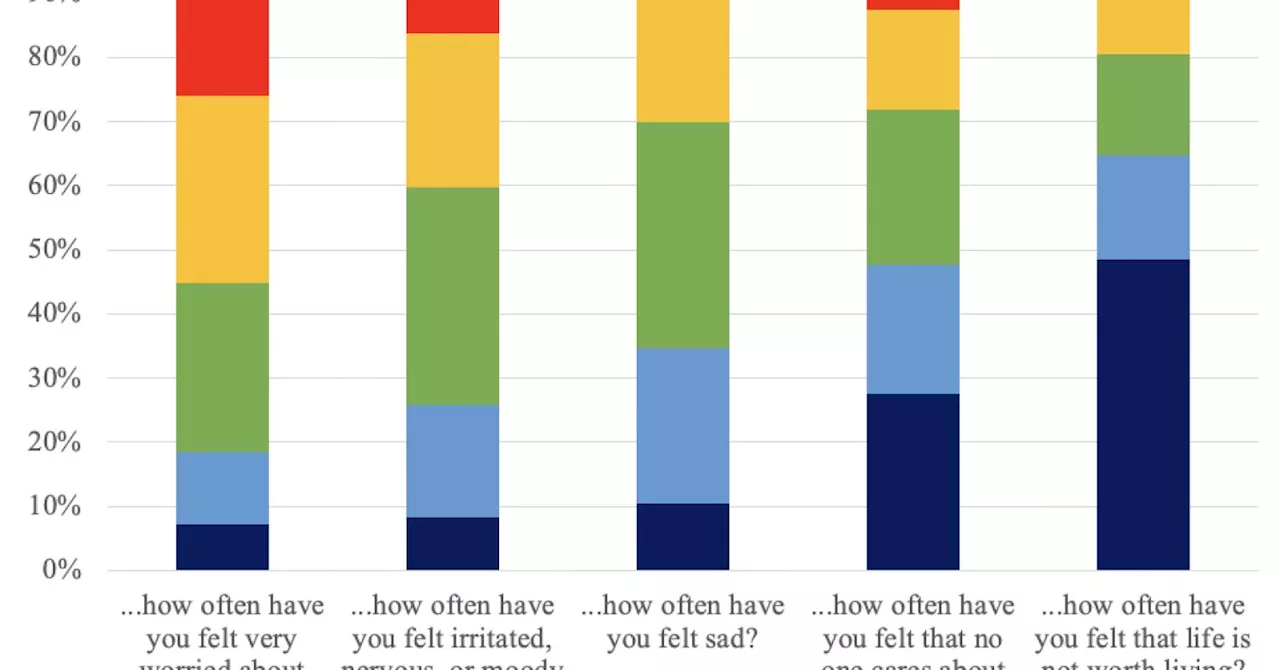

The study’s findings indicate that while most adolescents report few depressive symptoms, those who experience bullying or teasing are significantly more likely to report feelings of sadness and moodiness. Depressive symptoms were assessed based on students’ responses regarding their emotional experiences, with a considerable proportion indicating that they felt “never,” “rarely,” or “sometimes” sad. This suggests that the majority of adolescents are not experiencing severe mental health issues, which is encouraging.

Despite this positive outlook, the study highlighted a troubling statistic: between 13 percent and 40 percent of students reported experiences of peer victimization. Researchers sought to understand how these experiences influenced the mental health of adolescents. By analyzing the data, they found that peer victimization accounted for an additional 34.41 percent of the variance in depression scores among students, indicating a profound impact on mental well-being.

Understanding the Impact of Peer Victimization

The research underscores the critical role that school environments play in shaping adolescent mental health. As noted by the study’s lead researcher, Josafa da Cunha, a Professor of Educational Psychology at the Federal University of Paraná, the effects of peer victimization can be long-lasting and detrimental to students’ emotional well-being. Although many students reported minimal experiences of bullying, those who did were significantly more likely to suffer from depression.

The methodology involved students answering questions about their experiences of bullying in the past month, where they were asked whether they had been “bullied or teased so much that you were hurt, annoyed, offended, or humiliated.” The majority reported no incidents of peer victimization, which is a positive finding. Nevertheless, the concerning percentage of youths who did face such challenges points to a need for targeted interventions.

Research conducted previously has echoed these findings, demonstrating that peer victimization can lead to enduring negative effects on mental health. This current study provides compelling evidence of these trends within a large-scale and representative sample of Brazilian youth.

Pathways to Positive Change

In light of these findings, the importance of fostering positive school climates cannot be overstated. The study suggests that schools with lower levels of victimization correlate with reduced rates of depression among students. Consequently, efforts to create safe and supportive environments may significantly mitigate the adverse effects of bullying.

School administrators and educators are encouraged to continue their work in implementing measures to prevent bullying and support students’ mental health. The research team emphasizes the need for follow-up studies to explore how positive relationships between teachers and students can further shield youths from the psychological impacts of victimization.

Future research in developmental psychology is poised to delve deeper into the various ways peer interactions influence adolescents’ social experiences. By enhancing our understanding of these dynamics, stakeholders can better protect young people and promote healthier school environments.

Ultimately, the key takeaway from this study is the intertwined nature of peer victimization and depression among Brazilian adolescents. While many students navigate their school years without significant mental health issues, those who experience bullying are at a heightened risk for depression. Ensuring that every young person has access to a safe and supportive learning environment is essential for their growth and development.