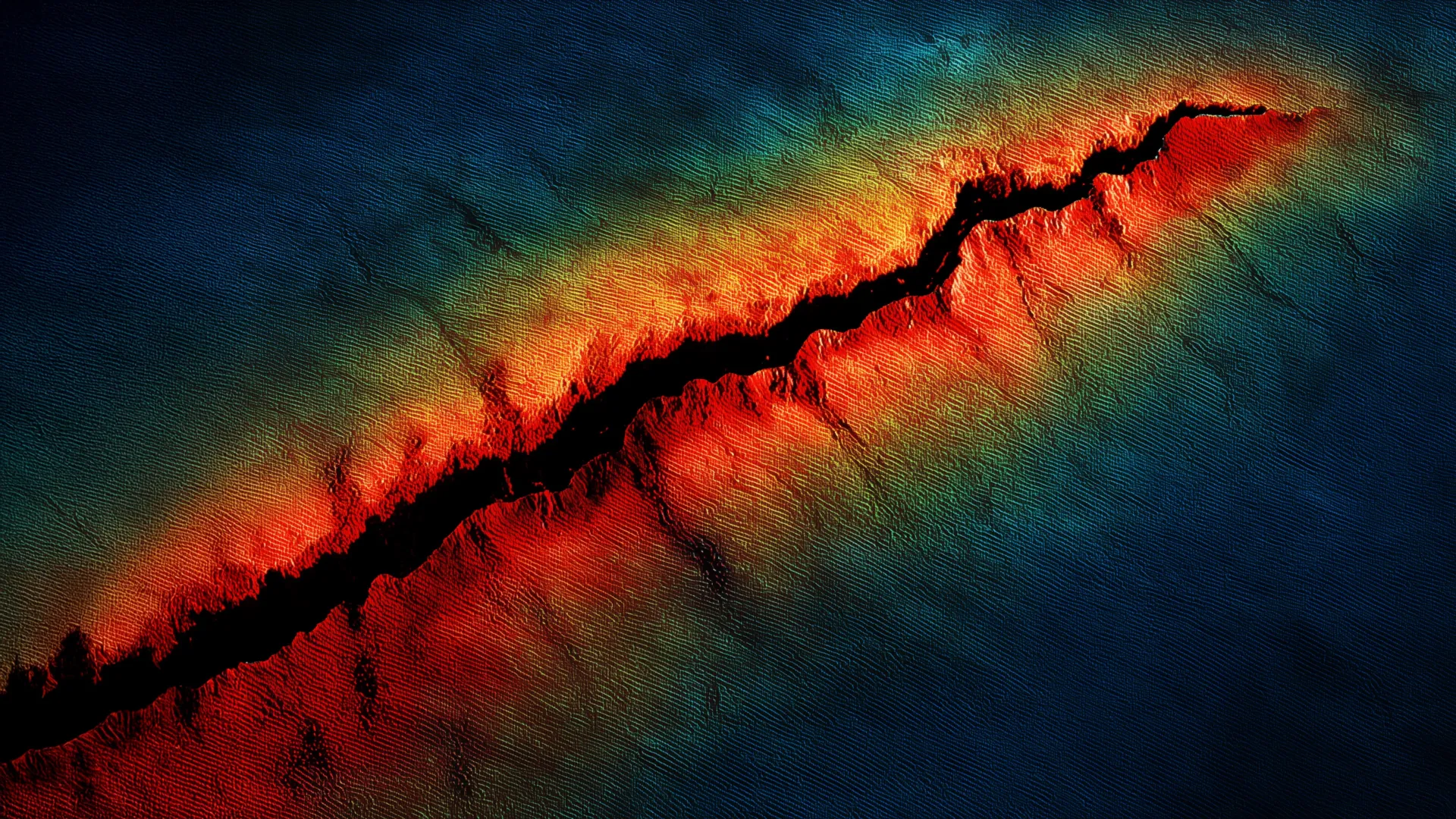

UPDATE: A revolutionary new method could drastically enhance how scientists assess earthquake risks. Researchers at Stevens Institute of Technology have developed a streamlined model that accelerates seismic simulations by a staggering factor of 1,000, making it easier for cities to prepare for potential earthquakes.

This breakthrough comes in light of the powerful 7.0 magnitude earthquake that struck Alaska on December 6, 2025. While predicting earthquakes remains elusive, this new approach promises to improve risk assessments significantly, ultimately aiding in disaster preparedness.

Every day, approximately 55 earthquakes occur globally, totaling around 20,000 annually, according to the United States Geological Survey (USGS). The financial toll from earthquakes is increasing, with a 2023 report estimating damages at about $14.7 billion each year in the United States alone. This is largely due to growing populations in earthquake-prone areas.

Currently, scientists use a technique called Full Waveform Inversion to map underground layers that influence seismic activity. This process, however, is computationally intensive, often taking several hours per simulation. Enter the collaborative effort of Kathrin Smetana, along with computational seismologists from Utrecht University and the University of Twente. Their innovative model reduces the computational burden without sacrificing accuracy, allowing for quicker evaluations of earthquake risk.

“We reduced the size of the system that you need to solve by about 1,000 times,” Smetana states. This interdisciplinary project highlights the importance of collaboration in tackling complex scientific problems.

While this new model does not enable precise predictions of when earthquakes will strike, it provides a more efficient way to map the subsurface, enhancing understanding of seismic risks. Improved subsurface imaging is crucial for assessing how earthquakes can impact different regions, which can lead to more effective emergency responses.

Moreover, this modeling technique may extend to simulating tsunamis triggered by undersea earthquakes, potentially offering critical information within the crucial hour before waves reach the shore.

As Smetana emphasizes, “There’s no way to predict earthquakes at this time, but our work can help generate a realistic view of the subsurface with less computational power.” This advancement is a significant step toward increasing earthquake resilience and preparedness in vulnerable areas.

Stay tuned for more updates on this developing story that holds the promise of transforming earthquake science and improving community safety.