Fossilized bones dating back between 1.3 million and 3 million years have revealed significant insights into ancient ecosystems, shedding light on prehistoric diets, diseases, and climate conditions. Researchers from New York University discovered thousands of preserved metabolic molecules within these bones, offering an unprecedented opportunity to understand the health and environment of ancient animals. The findings highlight a world that was notably warmer and wetter than today’s climate.

For the first time, scientists successfully examined metabolism-related molecules in fossilized remains, according to a study published in the journal Nature. The research team, led by Timothy Bromage, professor of molecular pathobiology at NYU, utilized advanced techniques to analyze chemical traces that provide a direct link to the biological processes of these ancient creatures. The results reveal not only what these animals consumed but also details about their health and the climates they inhabited.

Unlocking Ancient Ecosystems

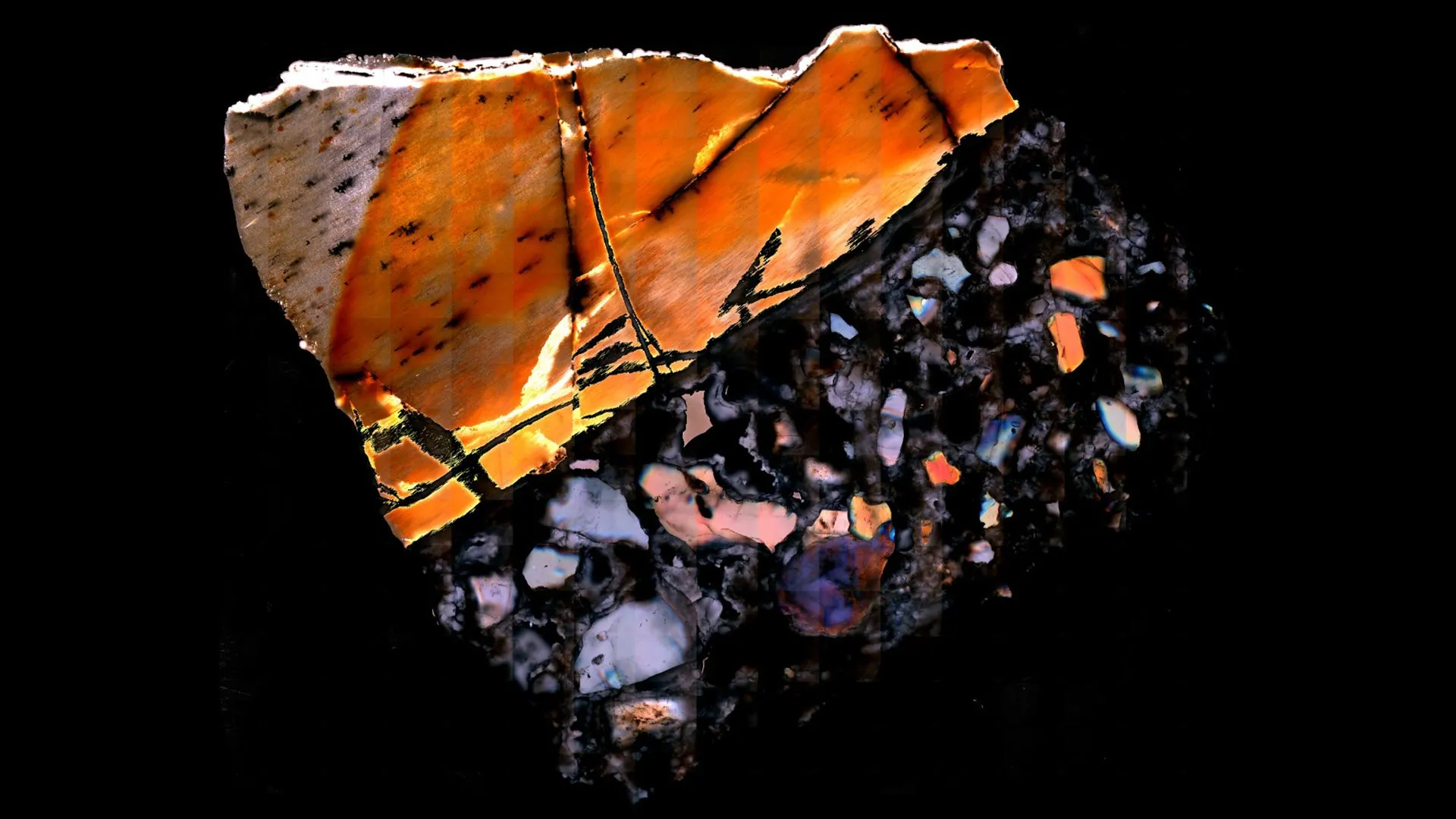

The fossilized bones, excavated from regions in Tanzania, Malawi, and South Africa, belonged to a variety of species, including rodents and larger animals such as antelopes and elephants. By employing mass spectrometry, the researchers identified nearly 2,200 metabolites in modern animal bones and successfully translated this method to their ancient counterparts. This innovative approach enables scientists to reconstruct the environmental conditions surrounding these animals.

The chemical analysis unveiled information about the health of the animals and the plants they consumed. Notably, one fossilized ground squirrel bone from Olduvai Gorge, dated to approximately 1.8 million years ago, exhibited evidence of a parasitic infection caused by Trypanosoma brucei, the same parasite responsible for sleeping sickness in humans. The discovery highlights how metabolites can reveal both dietary habits and health challenges faced by these ancient animals.

Climate Insights and Dietary Habits

The study’s findings indicate that the ancient habitats were significantly different from current conditions. The chemical evidence allowed researchers to identify specific plants consumed by the animals, such as aloe and asparagus. For instance, the presence of aloe metabolites in the ground squirrel’s bone suggests that it thrived in a wetter environment, rich in specific vegetation.

Bromage noted, “We can build a story around each of the animals,” as the reconstructed habitats align with previous geological studies. The research demonstrates a consistent pattern of wetter and warmer climates across all studied locations.

This groundbreaking research opens new avenues for understanding ancient life. By applying metabolomics to fossils, scientists can reconstruct prehistoric environments with remarkable detail. Bromage stated, “Using metabolic analyses to study fossils may enable us to reconstruct the environment of the prehistoric world with a new level of detail, as though we were field ecologists in a natural environment today.”

The research has gained significant attention, supported by The Leakey Foundation and the National Institutes of Health, which provided funding for advanced microscopy techniques. The collaborative effort involved contributions from scientists across various institutions in France, Germany, Canada, and the United States.

As researchers continue to explore these ancient remains, the potential to uncover further secrets about our planet’s history remains vast, transforming our understanding of life millions of years ago.