West Virginia is witnessing a significant transformation as data centers and bitcoin mining facilities establish themselves in the region, reminiscent of the coal industry’s historical impact. This new phase in economic development is altering local environments and community dynamics, often without the public’s awareness until the consequences manifest in utility bills or environmental changes.

The data center boom in West Virginia highlights a troubling trend. Companies are setting up operations in areas with minimal regulatory oversight, rewriting local rules to favor their interests. As noted by the National Conference of State Legislatures, at least 37 states have adjusted their tax codes and regulatory frameworks to attract data centers, offering billions in tax exemptions annually. West Virginia stands out as a state where these practices are particularly pronounced, echoing the historical exploitation seen during the coal era.

In many ways, this influx of data centers mimics the earlier coal mining boom. The environmental degradation associated with coal extraction is now being replaced with a different form of resource extraction, albeit one that is less visible. While coal left behind stark physical scars on the landscape, data centers often operate behind closed doors and are marketed as a cleaner alternative. For instance, Blockchain Power Corp. has announced the establishment of five bitcoin mining sites in previously abandoned coal areas, consuming approximately 107 megawatts of electricity to operate their specialized machinery. This power is necessary for maintaining a global ledger that updates every ten minutes, ultimately benefitting entities far removed from West Virginia.

Despite their significant energy requirements, data centers like these employ a fraction of the workforce that coal mining once did. In the case of Blockchain Power Corp., only 44 individuals are employed at their facilities, starkly contrasting with the hundreds of jobs previously created by coal operations. Communities are left grappling with the trade-offs of diminished resources—water, land, and power grid capacity—while receiving minimal local employment opportunities in return.

The narrative surrounding these data centers remains strikingly similar to that of the coal industry. Executives tout the region’s suitability for their operations, citing factors such as the “abundance of water in the Monongahela River.” They assert that their presence reduces the burden on residential customers, even as they draw substantial amounts of power from the same grid. The recently enacted Power Generation and Consumption Act, signed by Governor Patrick Morrisey in April, further exemplifies this trend by streamlining the regulatory process for such projects, allowing them to bypass traditional zoning and land-use restrictions.

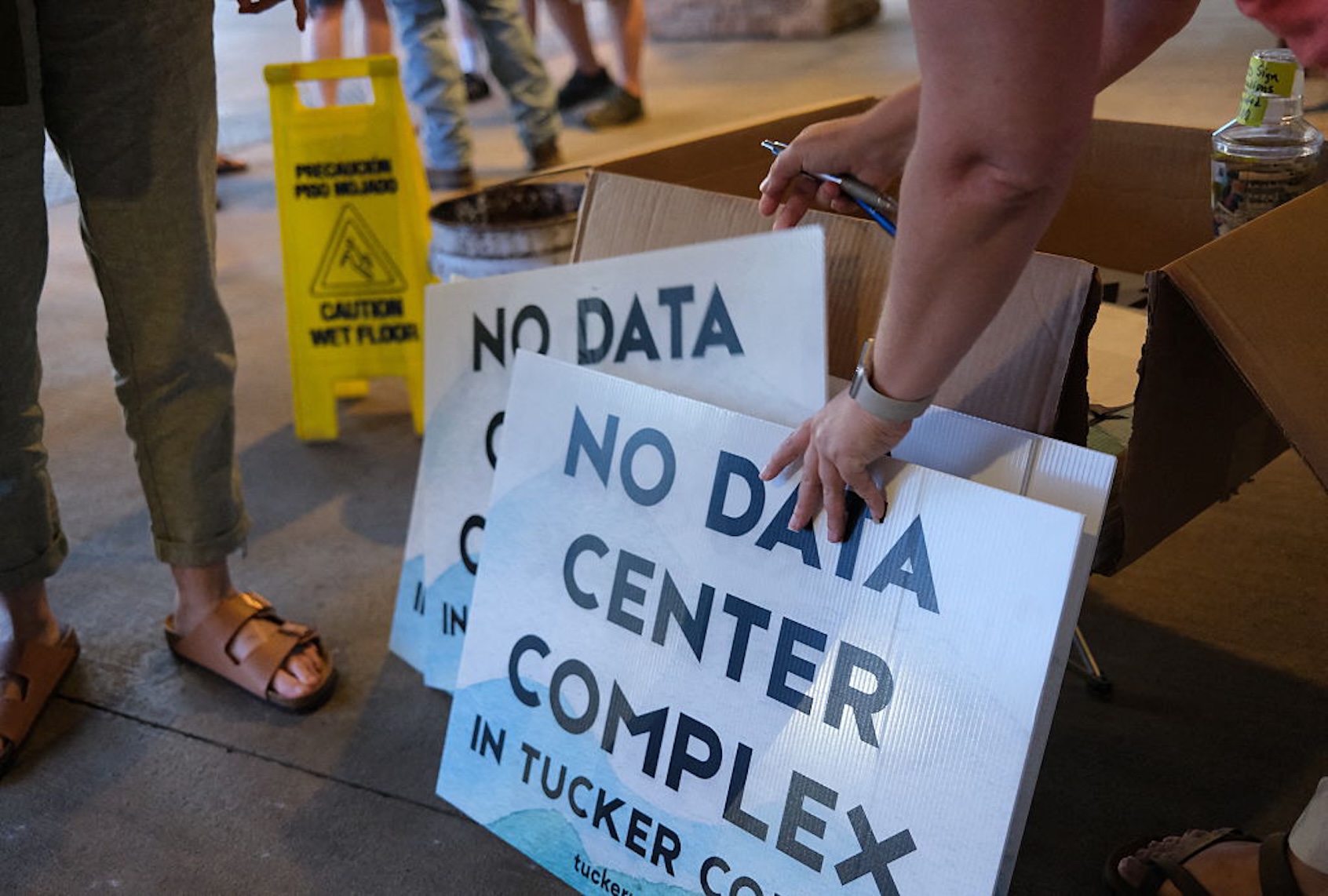

Currently, Tucker County faces the prospect of a private off-grid gas plant being constructed between the towns of Thomas and Davis. Residents are raising essential questions about the project’s impact on local water supplies, noise levels, and air quality, but often receive vague responses or redacted permits. Similar developments are underway in Mingo County, along with plans for additional data center complexes in Jefferson and Berkeley counties.

As documented by legal experts at Harvard University, the burden of increased power demand from industrial customers often falls on local residents, who ultimately face higher utility costs. West Virginia has seen this cycle unfold over the past century, with the promises of economic growth and job creation frequently overshadowed by the negative externalities of large-scale extraction industries.

Historically, coal companies would offer promises of prosperity, only to leave behind communities burdened with polluted environments and inadequate infrastructure once the resources were depleted. Now, data centers are extracting cheap electricity and water, converting them into profit through bitcoin and cloud services, often without contributing to the local economy. The shift from coal towns to data centers signifies a change in the nature of extraction but retains the same underlying issues of exploitation and neglect.

The political landscape in West Virginia is also shifting to accommodate these new industries. Local governments are stripped of power regarding zoning and noise control, allowing data centers to operate under minimal oversight. The same agencies tasked with regulating these developments often prioritize industry interests over public input, approving projects without sufficient transparency.

As these data centers establish themselves, communities are left with the challenge of understanding their long-term implications. Many residents are unaware of the operational demands placed on local resources until it is too late. The rapid pace of these developments often outstrips public opposition, as by the time residents learn of a new facility, the regulatory framework is already in place.

West Virginians have endured the consequences of previous industrial booms, including school closures and infrastructure damage without adequate financial support. The lingering memories of past exploitation shape how residents perceive new proposals. Any promises of economic renewal are weighed against a history of industries that have extracted resources while leaving behind a legacy of hardship.

The challenges posed by data centers raise critical questions about sustainability, economic viability, and community well-being. As the industry continues to evolve, residents and policymakers alike must consider the long-term effects of these developments and strive for a balance that protects local interests while accommodating growth.